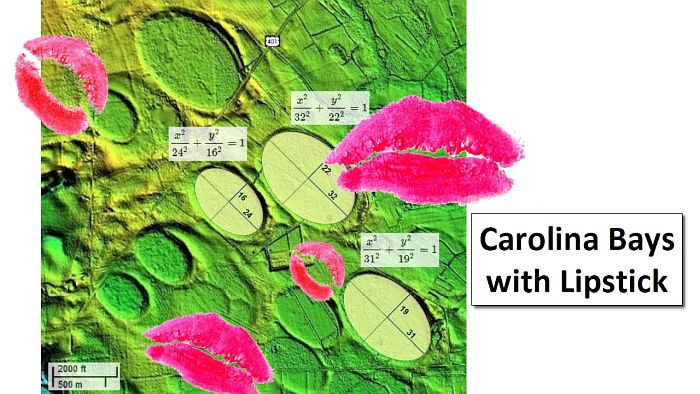

The Carolina Bays do not get the attention that they deserve in geology books. Putting lipstick on the Carolina Bays is not a bad idea for calling attention to these geological features that have been neglected and dismissed as unimportant for a very long time.

Transcript:

I am very disappointed that the Carolina Bays do not get the attention that they deserve in geology books, so to call attention to the bays, I am going to paint them with lipstick. A pig with lipstick is still a pig, but lipstick makes the pig more beautiful. Millions of dollars are spent each year on lipstick because the colorful lips attract attention and seem to say "look at me. I am beautiful." Lipstick is used to attract attention from the deepest jungles of the Amazon to the most luxurious fashion runways of New York, Paris and Milan, so putting lipstick on the Carolina Bays is not a bad idea for geological features that have been neglected and dismissed as unimportant for a very long time.

The Carolina Bays are elliptical geological formations oriented toward the Great Lakes. The bays occur on sandy soil close to the water table and they have raised rims. The interior of the bays is often swampy and the rims are made of sand from which the clay has been strained out by rainfall for thousands of years, making it whiter than the surrounding soil. The regular geometric shape and the systematic orientation of the bays was discovered soon after the invention of the airplane made it possible to view the Earth from a high altitude.

The introduction of LiDAR, which is a laser-based ranging technology, has made it possible to view the Carolina Bays without the interference of vegetation. LiDAR images clearly reveal the raised rims of the bays and the way in which the bays overlap while maintaining their elliptical shape. Topographic LiDAR images that are colorized based on the altitude relative to sea level can be admired as abstract works of art made by nature.

Photographic mosaics of the Carolina Bays in the 1930s caught the attention of professors Melton and Schriever from the University of Oklahoma. They investigated the bays and found four important characteristics, which were their smoothly elliptical shape, their parallel alignment in the southeastern direction, a peculiar rim of soil which is invariably larger at the southeastern end, and a mutual interference of outline that allowed one elliptical bay to partially overlap another one. Melton and Schriever proposed that an impact by a cluster of meteorites seemed the most reasonable explanation for these geological features.

Based on the width-to-length ratios of the elliptical bays, Melton and Schriever calculated that meteors striking plastic material at angles between 35 and 55 degrees from the vertical would produce indentations elliptical in outline. Even the ancient Greeks knew the relationship between cones cut at an angle and ellipses. This is why ellipses are called conic sections. In modern geology, inclined conical cavities made by impacts are called penetration funnels.

In 1952, Professor William Prouty published a paper about Carolina Bays and their origin. He examined all the evidence available at the time and conducted impact experiments with a high power rifle on various types of targets. Professor Prouty estimated that approximately 50 percent of the Atlantic Coastal plain was covered with Carolina Bays. He noted that the ellipticity of the Carolina Bays varied depending on the size of the bays. Smaller bays were less elongated than the larger bays. Prouty plotted a chart of the ellipticity of the Carolina Bays relative to the length of the major axis. The chart indicated that small bays had smaller ellipticity than larger bays, but they also had higher variability in ellipticity.

Today, we know that the Carolina Bays cover 100 percent of the Atlantic Coastal Plain. This is made evident by a LiDAR image 25 kilometers southeast of Fayetteville, North Carolina that shows a landscape completely covered with Carolina Bays, except where streams and rivers have carved fluvial channels for thousands of years after the emplacement of the bays. The LiDAR image also shows modern highways and train tracks as thin lines built upon a foundation of Carolina Bays.

In spite of the well documented evidence that the Carolina Bays are the dominant geological structures of the Atlantic Coastal Plain, many geology books do not mention them. The book about structural geology by Professors Ben Van Der Pluijm and Stephen Marshak does not have a single word about the Carolina Bays. This is bad for the future of geology because geology students will not even know that the Carolina Bays exist.

The book by Professor Jay Melosh entitled "Planetary Surface Processes" acknowledges the existence of the Carolina Bays, but dismisses them with contempt in one sentence. His textbook says: "Thawed permafrost expels water and contracts, sagging downward into small ponds that collect more water end enhance melting. Such thaw lakes are common, creating landscapes packed with kilometer-diameter circular to elliptical ponds that are often aligned with the prevailing wind. Such lakes constitute the infamous Carolina Bays, which impact crater enthusiasts persistently claim to be of impact origin in spite of the complete lack of evidence for impacts." Ignoring the Carolina Bays in geology books is bad enough, but it is much worse to implant in the minds of geology students that the Carolina Bays are "infamous" and that it is ridiculous to even consider their impact origin lest you become one of those foolish impact-crater enthusiasts. Such biases are difficult to overcome when they are advocated by a respected impact expert like Professor Melosh.

The idea that the Carolina Bays are not impact structures is supported by numerous attempts to date the Carolina Bays using Optically Stimulated Luminescence, or OSL, which is a very precise method of dating sedimentary terrestrial structures. The terrain on which the Carolina Bays are found has dates that range from a few thousand years to more than 100,000 years. Such diverse dates imply that the Carolina Bays could not have been created in a single event. However, Optically Stimulated Luminescence is intended for sedimentary structures, and if the Carolina Bays were created by impacts, OSL cannot be used to find the date of their emplacement. The dates obtained by OSL are simply the dates of the terrain and not the dates of bay formation.

A LiDAR image near Bowmore, North Carolina shows many well-preserved Carolina Bays, including some that overlap and some that are found within larger bays. The geological law of superposition states that newer structures overlay older structures. This provides guidance for determining the sequence in which the bays were created.

The debate over whether the Carolina Bays are oval or elliptical is over. Using the clear images produced by LiDAR, it is easy to show that well-preserved bays can be precisely fitted with ellipses, proving that the Carolina Bays are mathematical conic sections. If this could be shown for just a few bays, this mathematical attribute could be easily dismissed as just a lucky coincidence. But when the majority of the bays can be precisely fitted with ellipses, it ceases to be a coincidence and becomes a fact attributable to the mechanism of bay formation, which implies that the Carolina Bays originated as inclined conical cavities. The raised rims of the bays also correspond to the overturned flanges made by impact penetration funnels.

Opponents of the impact origin of the Carolina Bays attribute their formation to eolian and lacustrine processes, which is a fancy way of saying that they were formed by the action of wind and water. Such arguments usually ignore the fact that Nebraska also has elliptical structures with the same characteristics as the Carolina Bays. The Nebraska Rainwater Basins are oriented toward the southwest and occur on terrain that is 500 to 700 meters above sea level on sandy soil south of the Platte River. Nebraska has not been close to any sea since the Laramide orogeny started building the Rocky Mountains and drained the Western Interior Seaway more than 60 million years ago. The wind and water hypothesis cannot explain how the Carolina Bays and Nebraska Rainwater basins have such precise elliptical shapes and why extensions of the major axes of these elliptical features converge by the Great Lakes.

In 2017, a paper entitled "A model for the Geomorphology of the Carolina Bays" proposed that an extraterrestrial impact on the Laurentide Ice Sheet ejected pieces of glacier ice in ballistic trajectories and that the oblique secondary impacts liquefied the soil and created inclined conical cavities that were transformed into shallow elliptical bays by viscous relaxation. The paper was reviewed by two professional geologists and the editor of the journal Geomorphology before it was published.

This paper included photographs of experimental impacts of ice projectiles on a viscous target of sand and pottery clay. The images clearly show the penetration funnels created by the impacts. The ice projectile parts the viscous medium before coming to rest at the apex of the conical cavity. Looking at the impact structures from above, it is evident that the impact scars have an elliptical shape with raised rims, just like the Carolina Bays. So, regardless of what the experts say about the origin of the Carolina Bays, we have to trust the geometrical analysis and the experimental results.

I already mentioned two books that either ignore the Carolina Bays or call them "infamous". Searching the world wide web for Carolina Bays using Google or Microsoft Bing brings up the Wikipedia article as one of the first results. The Google search results also have a section about questions that people ask, such as "What caused Carolina Bays?" The featured answer is taken from an article in a North Carolina magazine called "Our State" that says that most scientists agree that only one theory holds water: As glaciers waxed and waned in regions north of us, water-filled depressions on our southeastern Coastal Plain expanded and contracted. Wind patterns created waves, forming sand deposits around the water's edge, and slowly, the bays began to take shape.

The Wikipedia article describes the Carolina Bays as elliptical to circular depressions concentrated along the Atlantic seaboard and mentions why the Carolina Bays are called Bays with a capital "B".

The Wikipedia article goes on to say that most geologists today interpret the Carolina bays as relict geomorphological features that developed via various eolian and lacustrine processes. Multiple lines of evidence, such as optically stimulated luminescence indicate that the Carolina Bays predate the start of the Holocene Epoch. The range of dates can be interpreted to indicate that Carolina bays were either created episodically over the last tens of thousands of years or were created more than a hundred thousand years ago and have since been episodically modified.

The Wikipedia article also states that recent work by the U.S. Geological Survey has interpreted the Carolina bays as relict thermokarst lakes that have been modified by eolian and lacustrine processes. Modern thermokarst lakes are common today around Barrow, Alaska, and the long axes of these lakes are oblique to the prevailing wind direction. These lakes develop by thawing of frozen ground, with subsequent modification by wind and waves. Thus, the interpretation of Carolina bays as relict thermokarst lakes implies that frozen ground once extended as far south as the Carolina bays. This interpretation is consistent with the optically stimulated luminescence dates, which suggest that the Carolina bays are relict features that formed when the climate was colder, drier, and windier. This is similar to what the book by Professor Melosh said.

The Wikipedia article mentions alternative interpretations of Carolina Bays that are no longer viewed favorably by most geologists, which include an extraterrestrial impact hypothesis. The article says that comet or meteorite impact hypotheses were popular during the 1940s and 1950s. However, geologists later determined that the depressions are too shallow and that they lack evidence for them to be impact features. The extraterrestrial impact origin of Carolina bays was proposed again in association with the Younger Dryas impact hypothesis, but the theory has been discredited by OSL dating of the rims of the Carolina bays, paleoenvironmental records obtained from cores of Carolina bay sediments, and other research related to the Laurentide Ice Sheet.

Sometime in the past, the Wikipedia article about the Carolina Bays had a reference to the 2017 publication in Geomorphology that said "Well-preserved Carolina Bays have close to exact elliptical shapes with width-to-length ratios averaging 0.58 and with long axes oriented toward the Great Lakes". The reference to this peer-reviewed publication was deleted with the comment "removed reference to nonexpert". In this way, all publications that claim that the Carolina Bays are impact structures are dismissed by deletion or placed in the alternative interpretations of Carolina Bays that are no longer viewed favorably by the scientific community.

The Carolina Bays cannot be evaluated without taking into consideration the Nebraska Rainwater Basins. The main characteristics of the Carolina Bays and Nebraska Rainwater Basins are: 1) mathematically elliptical geometry that corresponds to cones inclined at about 35 degrees, 2) raised rims that are characteristic of impacts because impact cratering displaces material by horizontal compressive forces and ejects debris ballistically to create stratigraphically uplifted rims, and 3) the radial orientation of the Carolina bays and Nebraska basins toward a convergence point by the Great Lakes. It seems fairly clear that these geological structures originated as oblique penetration funnels that were remodeled into shallow bays by geological processes like viscous relaxation. Optically Stimulated Luminescence is a technology designed for dating terrain deposited by sedimentary processes, and its use for dating a landscape formed by impacts is a misapplication of the technology.

The Carolina Bays are the most prevalent geological structures of the Atlantic Coastal plain. They should be in geology books regardless of whether they formed by wind and water mechanisms or by secondary impacts of glacier ice boulders ejected by an extraterrestrial impact on the Laurentide Ice Sheet. It should not be necessary to paint the Carolina Bays with lipstick to make them more attractive. The Carolina Bays are remarkable enough just as they are.